Arthur Rackham was born in 1867 into a Victorian age that he perpetuated and documented by way of his art. He was one of twelve children. He studied at the City of London School where he won prizes and a reputation for his art. At the age of 18, he became a clerk. It was, after all, a Dickensian world as well, where clerks played a significant role in both fiction and real life. He clerked and in his spare time studied at the Lambeth School of Art. He made occasional sales to the illustrated magazines of the day like Scraps and Chums. In 1891 and 1892, he had a close association with the Pall Mall Budget as one of this weekly's main illustrative reporters. He was competent.

Rackham's early work showed facility but little else. The humor and romance and soul that were to make him the premier illustrator of the early twentieth century had not manifested themselves yet. In 1892, he left his clerk position at the Westminster Fire Office for the uncertainty of a career as an illustrator. He landed a regular job at the Westminster Budget, a weekly magazine, that provided him with regular work as a reporter as he tackled the burgeoning book market. His first efforts were decidedly non-fantasy and are very indicative of an artist in search of a style. The image above right from the 1895 edition of Washington Irving's Tales of a Traveller owes as much to Howard Pyle or E.A. Abbey as to anyone else. Other Rackham illustrations (there were five) in the two-volume set are remarkably unlike this one and are stylistically vague. From book to book and image to image, one would be hard pressed to be certain the work was by the same artist.

His first book illustrations were published in 1893 and they were mostly reused images from magazines or books featuring the work of several illustrators (Tales of a Traveller is one such).The first book with illustrations done specifically on commission was in 1896. That book, The Zankiwank and The Bletherwitch (see image to right), to my mind marks the first hints of the lighter side of Rackham. Maybe it was all that "clerking" and the discipline required as a reporter, but his early work is stiff and, frankly, boring. If it didn't have his name on it, I wouldn't look at it twice if I saw it in a magazine. The Zankiwank... isn't high fantasy art, but there are images that presage, if not greatness, then at least the joyous frivolity that was to be an important component of his work. Also evident is the influence ofCharles Robinson, whose A Child's Garden of Verses had been released to much acclaim the year before.

Nineteen more book assignments followed during the 1890's, with dozens of pictures for two major children's magazines: Cassell's and Little Folks and even one for the venerable St. Nicholas. It's intriguing to watch the progression of subject matter of the books during this period. His second book was In the Evening of His Days. A Study of Mr Gladstone in Retirement, his third Bracebridge Hall by Washington Irving. His fourth and sixth were The Money-Spinner and other Character Notes and Captain Castle. A Tale of the China Seas. He did another boy's adventure book titled Charles O'Malley, The Irish Dragoon, and several books on English Gardens and hunting and fishing. Not really the stuff of fantasy and fairy tales, but there was The Ingoldsby Legends in 1898 (with 12 color plates and 80 line drawings - like the skeleton at left!) and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm in 1900 (with a color frontispiece and 95 pen & ink drawings). By far his greatest efforts were being expended in the service of fantasy - at least if you only count quantity. The Ingoldsby Legends, by the way, was radically revised and updated in 1907.

From 1900 to 1904, it was pretty much more of the same: gardens, golf, cricket, bird watching, farming, shooting, Two Years Before the Mast, and several boy's books like Mysteries of Police and Crime, The Argonauts of the Amazon, and Brains and Bravery. While the subject matter remained fairly constant, Rackham was developing a style that was not only his own, but was to influence a generation of children and artists. The roots of the style were surely evident in many of the books listed above, but the flowering took place in 1905 in a stunning edition of the old Washington Irving classic, Rip Van Winkle.

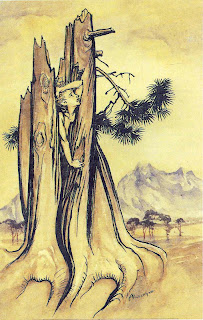

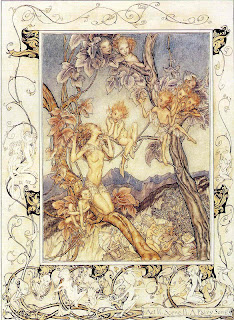

It was Rackham's first major book (see image at right). The publisher, William Heinemann, knew it had a sure best seller. Rackham painted 51 color plates, tipped-in and gathered together at the rear of the book. They featured all of the traits that were soon to be as famous as his signature:

a sinuous pen line softened with muted water color

forests of looming, frightening trees with grasping roots

sensuous, but somehow chaste, fairy maidens (at right)

ogres and trolls ugly enough to repulse but with sufficient good nature not to frighten

backgrounds filled with little nuggets of hidden images or surprising animated animals or trees

Most obvious, in retrospective, is the calm and good humor of the drawings. They seem imbued with a gentle joy that must have been reassuring to both the children and their parents. Rackham had found his niche. His drawings would convey a non-threatening yet fearful thrill and a beauty that was in no way overtly sexy or lewd. It was a perfect Victorian solution and he seems to have taken to it with an impish delight.

To touch on just few of the literally dozens of highlights of a long and successful career, Rip was followed in 1906 by one of his two masterpieces,Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, another 50-plate extravaganza - this from Hodder and Stoughton. A great sample of his foreboding trees is at left - from Peter Pan.

1907 saw an edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland from Heinemann. J.M. Dent reissued Ingoldsby and Constable & Co. Grimm, both in revised, updated editions. "Rackham" was a marketable commodity and everybody wanted one of the golden eggs. It appears that Heinemann won the goose, though. In rapid succession, amid a wealth of other books (some minor, some important), they published four books intended for adults: in 1908 - A Midsummer-Night's Dream (which I classify as his second masterpiece); in 1909 - Undine; in 1910 and 1911 The Rhinegold and the Valkyrie andSiegfried and The Twilight of the Gods. These four books contained 115 color plates from Rackham's paintings and all of my favorite Rackham images are contained within them.

In his 1994 A New Bibliography of Arthur Rackham, Richard Riall relates,

"..years ago I went to an antique fair, and there was a selection of old books on a stall. I looked idly through the assorted illustrated books and came to Siegfried & The Twilight of the Gods. This book was not a first edition, it was in a terrible condition and finally it was far too expensive. I bought it, and was so enchanted with the illustrations that I ignored all the faults... I still have this copy."

I have a similar story. In the early 1970's I frequented a musty store called The San Carlos Book Store, about 12 miles from my apartment home. They had a large black bird just inside the door that would give out a piercing wolf whistle or cheerfully inform you that "birds can't talk" when you entered the store. In a small annex accessible only through a locked gate was the sanctuary of Mr. Maierfeld, who dealt in rarities. My truck was with the small novels selling for $3 with a few Flanagan or Cornwell b&w plates. When I finally got up enough nerve to beg admission to the inner sanctum, I felt very out of place. Still I made the most of it and explored a treasure trove of marvelous things. One thing I picked up was the companion to Riall's first Rackham experience - Siegfried. Mr. Maierfeld's The Rhinegold and The Valkyrie happily (I say that today) was a first edition andwas in collectible condition. It also was $55, which was probably about ten times what I'd ever paid for a book to that time. I bought it. I don't think I ever set it down after I picked it up and saw the illustrations. I, too, still own my first Rackham and it remains one of my favorites - and not simply for sentimental reasons.

During those years, 1908-1911, he was simply at his peak. Above left is an illustration for the American magazine, The Century, for a 1911 article on The Training of English Children. Who better to provide the illustrations (there were two) then the man who was providing them (and their parents) with their entertainment? Who could capture the rocky beach and the very British bathing costumes, the impishness of the boy and loveliness of his sisters. Rackham found the poses to show the bearing and breeding that the article meant to convey.

Komentarų nėra:

Rašyti komentarą