Key Ideas

Clement Greenberg was instrumental in the rise to prominence of the entire Color Field school and felt that Olitski was, "the greatest painter alive," even as late as 1990. With his support, Olitski became one of the most famous painters in America during the late 1960s.

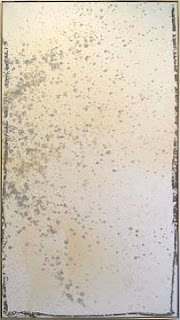

Oltiski wanted to create paintings that looked like, "nothing but some colors sprayed into the air and staying there." With this intention, he began to experiment with spray guns in 1965, a technique which allowed him to remove the illusion of depth to an even greater degree than possible with techniques like staining.

Olitski reached the zenith of his fame in the late 1960s, during which he represented the United States at the 1966 Venice Biennale, and was the subject of a solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Olitski's star fell quickly in the 1970s when he returned to a more traditional form of Abstract Expressionism, and with the exception of Greenberg, his reputation among critics never fully recovered.

DETAILED VIEW:

ChildhoodJules Olitski was born after his Bolshevik father was executed by the White Russian army in Snovsk, Ukraine in 1922. Soon after, his mother escaped with him to the United States and started a new life in Brooklyn, New York, where she remarried in 1926. Born Jevel Demikovski, he adopted the name of his mother's new husband, Hyman Olitsky, but disliked his stepfather greatly. He changed the last letter of his surname later in life after a clerical error.

Early TrainingOlitski showed an early talent for drawing and began taking art classes in the city during his teens. Olitski grew up in a very modest household and in 1939 he won a scholarship to the Pratt Institute. He studied at the National Academy of Design until 1942, during which time he also took classes at the Beaux Arts Institute on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. He served in World War II after completing his studies, which allowed him to attend the Ossip Zadkine School in Paris on the G.I. Bill. This funded the education of many other artists destined to become major members of the second generation of Abstract Expressionism. While in Paris, Olitski also studied at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere, having his first one man show at the Galerie Huit in 1951.

Olitski moved back to New York in 1951 and began studying at New York University, where he earned a B.A. in Art and an M.A. in Art Education in 1954. He took a position as the head of the fine arts division at C.W. Post College of Long Island University in 1956, where he remained for seven years.

During this time, Olitski began to receive recognition in New York as an artist. He exhibited at Iolas Gallery in 1958, and in 1959 he held his first one man show in the city at French & Co. gallery, where the renowned critic Clement Greenberg was a consultant. Greenberg became his steadfast champion and guided his career to its zenith.

Mature PeriodBy the late 1950s, the gestural abstraction of the New York School began to give way to a group of younger painters who reacted against Action Painting, with its heavy impasto and distinctive brushstrokes. They sought to remove evidence of the hand of the painter in a style dubbed, 'Post-painterly Abstraction', by Clement Greenberg. Olitski, along with Helen Frankenthaler, Ellsworth Kelly, Kenneth Noland, and Morris Louis were the pioneers of this movement. One branch of Post-painterly Abstraction, of which Olitski was a part, employed techniques that included staining the canvas with acrylic pigment to create works called 'Color Field' paintings. Color Field painters stained the actual surface of the canvas, which eliminated the illusion of depth to an even greater degree than their forebears.

When discovered by Greenberg, Olitski was creating monochrome canvases in an Abstract Expressionist idiom influenced by painters like Hans Hofmann. However, in the following years he began using a variety of colors and new techniques marked by experimentation with media and method. His experiments with staining the surface of the canvas can be seen in works like Cleopatra Flesh (1962), which feature the bright dyes that mark his work of that period. During the 1960s, Olitski changed his style rapidly. In 1964 he began using rollers to press paint into the canvas in wispy sheets of almost uninterrupted color, like in Tin Lizzie Green (1964). The surface is broken only at the edges, where Olitski used masking tape to cover the borders, and later painted another color.

Olitski's most important breakthrough came in the Spring of 1965, when he began using spray guns to apply paint. The process of laying down an unprimed, unstretched canvas and spraying simultaneously with several guns was groundbreaking. It removed all vestiges of drawing and the artist's hand. It was considered by some critics - including Michael Fried in his introduction to Olitski's 1967 show at the Corcoran Gallery - to be the apotheosis of the Color Field movement because it, "[made] possible the interpenetration of different colors, the intensity of each of which appears to fluctuate continuously," more fully than any other technique before. Fried went on to say that this interpenetration of color created a new sensation of depth in modern art, "by atomizing color Olitski has atomized, even disintegrated, the picture surface as well." This elimination of depth and new understanding of the picture surface comes closest to Olitski's own intention that his paintings resemble, "nothing but some colors sprayed into the air and staying there." These works, like End Run (1967), were very well received by critics and are considered the most important of Olitski's career.

With Greenberg's support, Olitski became a major player in the New York avant-garde and was chosen to represent the United States, along with Frankenthaler, Kelly, and Roy Lichtenstein, at the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966. For the introduction to the catalogue, Greenberg heaped praise upon Olitski in particular, who he said, "has turned out what I don't hesitate to call masterpieces in every phase of his art." Olitski's star continued to rise throughout the late 1960s as he was the subject of a major exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery in 1967, and received the honor of having a solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969.

However, in the early 1970s Olitski changed his modus operandi yet again and began applying paint in a thick impasto, which hearkened back to the gestural abstraction of his predecessors. Though he had a major show in 1973 at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts that also traveled to the Whitney, the tide of critical opinion began to turn against Olitski. By the mid 1970s, Post-painterly Abstraction had been challenged by Pop, Minimalist and then Conceptual art. Olitski continued to paint as he liked, and his persistence resulted in harsh reviews from critics like Hilton Kramer, who wrote that in the 1973 retrospective, "the only [works] that remain of interest are the [ones] he was producing in 1962." Equally negative critical response to his forays into sculpture relegated Olitski to the sidelines of the American avant-garde over the protests of Clement Greenberg. The critic's continued assertion that Olitski was the best living American painter - which he maintained until 1990 - probably hastened the decline in Olitski's stature among other critics, and his younger peers.

Late Years and DeathThough Olitski might have reached the zenith of his fame in the late 1960s, he was not discouraged by the largely negative critical response to his work in the 1970s and 1980s. He did not return to the spray guns which garnered him so much acclaim, but instead continued to experiment, employing mops and even his fingers to apply paint. During the two decades following his 1973 retrospective, his work saw a large decrease in major exhibitions, and a severe downturn in sales.

Undeterred, Olitski became heavily interested in printmaking and devoted a great deal of his time to this medium and to works on paper, often in watercolor. His later paintings are generally landscapes of the areas around his homes in New Hampshire and Florida, where he worked for the last several decades of his life. This return to the depiction of the natural world was a major departure from a career that avoided any recognizable imagery in favor of pure abstraction.

He began a final series of bright, forceful abstractions in the two years before his death, which were exhibited at galleries in New York and received many positive reviews, even from Hilton Kramer. Olitski painted until his death from cancer in 2007 at age 84.

LegacyThough Olitski continued to exhibit work until his death, he never reclaimed the fame he achieved forty years earlier. His groundbreaking work in the Color Field school of Post-painterly Abstraction - especially his spray paintings from the mid1960s - is still widely admired and studied, but not to the degree of his colleagues Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis. His place in art history is perhaps influenced by his spectacular rise and fall, and by Greenberg's persistent support of his status as "the greatest American painter" long after his prime.

Late Years and DeathThough Olitski might have reached the zenith of his fame in the late 1960s, he was not discouraged by the largely negative critical response to his work in the 1970s and 1980s. He did not return to the spray guns which garnered him so much acclaim, but instead continued to experiment, employing mops and even his fingers to apply paint. During the two decades following his 1973 retrospective, his work saw a large decrease in major exhibitions, and a severe downturn in sales.

Undeterred, Olitski became heavily interested in printmaking and devoted a great deal of his time to this medium and to works on paper, often in watercolor. His later paintings are generally landscapes of the areas around his homes in New Hampshire and Florida, where he worked for the last several decades of his life. This return to the depiction of the natural world was a major departure from a career that avoided any recognizable imagery in favor of pure abstraction.

He began a final series of bright, forceful abstractions in the two years before his death, which were exhibited at galleries in New York and received many positive reviews, even from Hilton Kramer. Olitski painted until his death from cancer in 2007 at age 84.

LegacyThough Olitski continued to exhibit work until his death, he never reclaimed the fame he achieved forty years earlier. His groundbreaking work in the Color Field school of Post-painterly Abstraction - especially his spray paintings from the mid1960s - is still widely admired and studied, but not to the degree of his colleagues Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis. His place in art history is perhaps influenced by his spectacular rise and fall, and by Greenberg's persistent support of his status as "the greatest American painter" long after his prime.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Komentarų nėra:

Rašyti komentarą